Screening procedure at schools for the blind in developing countries

In developing countries there are very different health care systems. For places where there is vision screening as a part of basic health care, this section is not pertinent. In many countries even the children at schools for the blind have not been properly assessed. In such circumstances the screening technique presented here will be useful.

First ask the child whether (s)he can see any light. If the answer is "no", give him a flash light to hold and ask whether he can see any difference in the lamp between when the light is turned on and when it is turned off. You may also show the child a nearby window and ask whether there is any difference when he is facing the window or facing the room. (A child, who has never discussed vision, may have difficulty in understanding these questions.) Since there is the possibility of misunderstanding, a person who knows the child, may be asked for further information. Also, observations can be made as a part of a usual school day. - If the child seems to be unaware of the presence of light sources, (s)he belongs to Group Ia, Total Blindness.

If the child can see light, ask which direction it comes from. Children, who perceive the presence of light but cannot tell which direction it comes from, belong to Group Ib, Light Perception Without Projection. Children who can locate the source of the light, but do not see the form presented in the next test situation, belong to Group II, Light Perception with Projection. The difference between these two groups, Group Ib and Group II, may seem small but the location of light facilitates orientation and mobility.

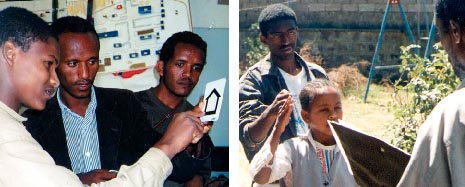

Screening exercises during a course on vision impairment and disability in Addis Ababa in February 1997: screening into Group II or III and measurement of visual field by using confrontation technique.

A child who can locate the source of a light, is presented with the LEA-Symbols response cards (=key crads) or large copies of optotypes of another test, one at a time, at close distance. If (s)he can see any of the forms, (s)he belongs to Group III or Group IV. The difference between these two groups is that persons in Group III do not see the 3/60 symbols at the standard test distance whereas those in Group IV do. The LEA-Screener is for measurement at 4 meters, therefore the largest symbol is 40M in size. The four meter distance was recommended in the ICIDH-2 (which will be called ICF when completed) as the standard measurement distance for adult persons and older school children. (ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health was published in 2001.)

Show the largest symbols at the distance of 4 meters. If the child cannot see them, move closer until the child sees 3 out of the 4 symbols correctly. If the distance is less than two meters, the child belongs to Group III; if it is longer, the child belongs to Group IV. Similarly, if the LEA-15-line folding chart is used, show it at 3 meter distance, then move closer until 3 out of the 4 symbols are recognised. If the distance is less than 1.5 meters the child belongs to Group III; if it is longer, the child belongs to Group IV.

In places where there is electricity available, the small lightbox allows measurement of visual acuity at a standard luminance level recommended by the National Eye Institute in the United States. It can be used at any distance, also to measure visual acuity at low contrast levels.

Visual field is measured by bringing the tester's hand from behind the child while the child is looking straight ahead. The fingers of the hand are moved because the peripheral visual field is sensitive to seeing movement. If the visual field is constricted to a small central tubular field of only ten degrees the child is reported as "blind" or Group III even if visual acuity is still good, and as having low vision if the visual field is less than 20 degrees in diameter but larger than 10 degrees. The size of the tubular field is measured during the assessment using white paper at a distance of 57 centimetres).

The limit of normal vision is difficult to define in the screening situation because the visual acuity tests used in screening and the size of the visual field do not reveal cases in which visual acuity is still normal but contrast sensitivity, central visual field or visual adaptation (night vision) are abnormal. Therefore we need other screening techniques for example in screening deaf children who may have Usher Syndrome. To screen for this disorder, we have to use measurement of midperipheral visual field and cone adaptation to identify the disorders of retinal function. Children with motor problems may have normal visual acuity but poorly controlled eye movements, which means that they must use specific reading techniques for learning.

These examples demonstrate that regular vision screening, based on visual acuity and the size of the visual field, may fail to identify some children who are visually impaired. This occurs particularly often among children with intellectual deficiencies, who are not tested with appropriate tests (='not testable children'), among children with motor problems because their higher visual functions are not tested and among deaf children because their risk of having retinal degeneration is not generally known and therefore not searched for.

At the schools for the visually impaired a basic evaluation of visual functions of all children reveals the number of children with different educational needs. As a example of such an evaluation is the report from Kenya.

Each child who has difficulties in learning should receive a full assessment of visual and auditory functions before any decisions are made on the IEP. Vision impairment of children with several impairments is discussed in PART II.

Previous Chapter

|

Next Chapter Next Chapter

|