9. Assessment of vision for educational purposes and early intervention

In the assessment of vision for learning at all ages we need:

- basic information from the child's doctor

- testing in day care and at school

- observations on the effect of posture when the child has severe motor problems

- assessment of compensatory techniques/skills

Vision for learning (see slide 20) needs to be assessed several times during the first year and, in case of an older child after an accident several times during the first few months. The development may be rapid and thus supportive functions and training need to be adjusted. It is important that we assess visual functions for all areas of development, not only for the academic skills.

There are four main areas in our functioning where vision is important: communication, orientation in space and mobility, activities of daily life and sustained near vision tasks like reading and writing.

Communication uses visual information that adds emotional content to the information given through speech. During the first three years it is the dominant avenue of information and therefore needs to be assessed at regular intervals. When the children come to teenage their communication becomes again very visual. They say one thing and their body language and expressions may tell the opposite thing. This age is therefore particularly confusing to visually impaired children who do not see well enough to perceive expressions.

O&M instruction is usually started at the age of three or four years but the foundations are built much earlier. If the infant has had an opportunity to assess small spaces ('little rooms') and has developed both body awareness and awareness of space around, motor development and orientation in space can be built on these functions. In extreme cases, orientation in space may be very poor in teenage, yet trainable.

Orientation in space is usually thought as a function in the allocentric space. Orientation in the egocentric space is equally important as shown in slide 85. We usually talk about eye-hand coordination but there are also tasks to find, to organise objects in certain places and to build structures out of blocks etc. In children with motor and visual impairment there are special problems in midline.

Eye movements across the midline may be difficult, using eyes and hands in midline may be much more difficult than on either side, which is opposite to normal functioning.

Eye-hand-coordination may be disturbed by a poor visual feed-back loop: The child looks at an object, turns eyes and head away and then reaches for the object. If asked to look at the object when reaching for it, the movement is less well controlled than when not looking at the hand movement. Hand movement may be smoother when the eyes are closed. The head may not need to be turned.

ADL, activities of daily living are the functions that are least well taught to visually impaired children in nursery schools and mainstream grade schools. It is not understood that visually impaired children need to learn special techniques to master situations that sighted children learn by watching what older children and adult people do. When visually impaired children do not perform at 'age appropriate level' they are diagnosed as having delays in their development, although they have not been given an opportunity to train the skills tested. Vision for ADL tasks needs to be assessed separately and the teachers need to know when special skills require consultation of an experienced teacher. Since many visually impaired children have also motor impairment, both ADL and O&M training must consider both impairments.

Sustained near vision tasks are usually best fitted to the child's needs and capabilities although measurement of visual acuity still may be made with only single symbols, especially in the younger children and thus magnification needs are not properly assessed. Use of telescopes is not trained as much as would be wise. Since visual impaired infants cannot study structures in environment when passing by them, we should use videos and pictures to teach them about their environment.

Basic questions is our assessment are as stated in this slide:

How does visual impairment affect a particular function now?

How is it going to affect development to the next level?

Does the child have adequate compensatory functions to compensate for visual disability? Who teaches compensatory functions and does (s)he know the child's visual capabilities well enough?

Graphic presentation of the techniques that a school child uses in the four main functional areas often is helpful when the IEP is discussed with the administrative persons who make the decisions on payments. They often question the need of services if the child functions like a sighted child even in one area. This diagram depicts functions of a deaf child with RP and clearly shows in which areas she has need of special training.

Follow-up of the development of special skills is not well covered in many mainstream schools because the special skills have not been defined and special training has not been arranged. This list of skills functions in many countries but needs to be modified in those countries where the cultural setting is different. It is at the end of PART I in the Manual "Assessment of Low Vision for Educational Purposes and Early Intervention". If the questionnaire is filled at the beginning and end of each term, it makes the teachers and parents aware of the areas where additional teaching is needed.

Ergonomics has not yet been mentioned although it is a big problem in the life of many visually impaired children. The short reading and writing distance should be balanced by a tilted desk surface and use of computers, which also need to be placed at correct height and close enough. Children with motor and visual problems need to work with their occupational therapists to solve ergonomic problems.

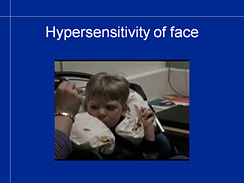

Compensating functions are equally important to assess as the visual capabilities. If the child is severely visually impaired and learning is based on auditory, tactile and haptic information, the compensatory modalities are more important than the impaired modality. Therefore they should be assessed at the time of diagnosis and supported during early intervention. Children who have hypersensitive hands, mouth or face need a lot of therapies to start to tolerate the use of compensatory informations.

Intermodal functions or integration of information from the different modalities is the goal of therapies. However, if visual information has not been used during the early months of life, it may not be used together with other modalities later in life. The normally sighted child uses visual information to organise information from the other modalities, a severely visually impaired child may add visual information to a basically auditory-tactile world. If tactile information dominates during the first year, visual information may never get its usual role in the brain functions. Therefore it is so important that even limited vision is used and that refractive corrections are given early.

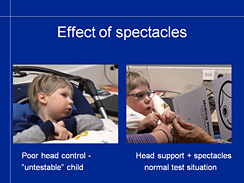

Before the assessment it is important to arrange positioning and supporting so that the child can participate in the test situation. Spectacle correction should match test distance if accommodation is weak. Many children have sensitive skin; placing the spectacles disturbs the short time when the spectacle frame moves. The reaction of the child (video) should not be interpreted so that the child does not want to have spectacles. Hypersensitivity can be decreased by rubbing the skin with first soft materials wrapped on the child’s hands and then slowly increasing the roughness of the material.

When supporting and spectacles function optimally, a child who could not be assessed because of poor head control and lack of glasses suddenly functions age appropriately.

We face new challengies when the number of visually impaired children in mainstream education increases and more and more severely multi-impaired children are in large groups of children in day care centres and in regular classrooms. Day care personnel and teachers and teachers' aids should receive more and better information on the children's functional capabilities and learn more about vision in their basic schooling if we want to give visually impaired children proper care and education. Well informed, they can participate in the assessment and add many valuable observations that can be made during teaching and play and not in the medical examinations. The concept of transdisciplinary assessment should become a reality.