Assessment of Visual Functioning of Disabled Infants and Children

as

Transdisciplinary Team Work

Lea Hyvärinen, MD, PhD, FAAP

14e Symposium scientifique sur l’incapacité visuelle et la réadaptation,

7 février 2012, Montreal

The questions related to early intervention, especially during infancy, have always been important to me because the studies with my late husband’s group on the plasticity of cortical functions during binocular visual deprivation in monkeys1 - 3 clearly showed that if vision is not used during early development, it loses its presentation in higher visual and associative functions and the monkey, and also the child, may be functionally blind or severely visually impaired, even if the eyes are structurally and functionally normal. The first year is the most important year of a child’s life in many areas of development of vision and vision related functions, especially in the development of communication, emotions, interaction, and motor functions.

The assessment of visual functioning of children with vision loss has become more demanding than before despite the fact that the last 30 years have seen a fast development of tests, devices, and observation techniques. The increased demand in the assessments is related to the greater complexity in the damage to the brain in infants and children. Infants born prematurely, even very small infants, survive despite of retinopathy of prematurity, brain damage, pulmonary changes, problems in swallowing, and severe hypotonia. Severe infections and traumas are now less fatal than before and often cause changes also in the visual system. In Western countries, infants and children with brain damage related atypical visual functioning are the largest group (20 to 25%) of children with impaired vision. They have many other disorders that affect use of vision directly and also restrict other functions. Changes in visual perception in the visual and associative cortices are difficult to assess and very difficult to describe in detail so that specialists in medicine, education and social services could understand and agree on the nature and severity of the child’s functioning and disability.

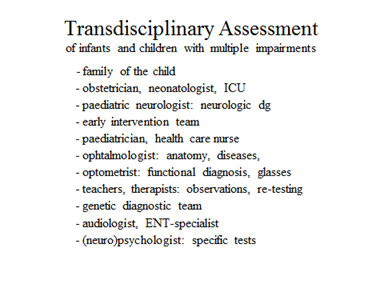

Slide 2 and 3.

The transdisciplinary team of a child with visual impairment usually includes 1) medical specialists in the hospital: obstetrician, paediatrician, paediatric neurologist and ophthalmologist, often numerous other specialists and their teams of nurses, technicians, and administrative personnel; 2) an early visual intervention team or support of visual development is included in the general early intervention, 3) social services, and later 4) education services both at the local school and in the educational resource centre.

In the transdisciplinary team, the family of the infant or infants, later child or children, is an important part. The parents, siblings, and their extended family go through periods of mourning the “death of the perfect baby” until they realize that few infants and children are perfect, also a less perfect baby can be loveable and enjoyable. The trauma is less crushing if the family gets support and positive information during the first days and weeks. New-born infants with atypical visual functions have many other problems that often require immediate treatment and therefore the baby cannot remain with the mother during the emotionally delicate moments after the birth.

Too many parents remember with bitterness the first hours and days of the infant when every time a person came to their room they heard a new negative comment of their baby, something seriously wrong and requiring further examinations, blood samples and painful treatment. The first information and the experiences in the hospital are crucial for the well-being of the family and should be taken care by experienced doctors and nursing teams to decrease the trauma.

Birth of an infant with any kind of deviation from norm is a risk for the parenthood and family. Families break more often than average families if the early care of their infant is demanding. Often the father disappears from the picture/ scene (better expression needed?), perhaps because he has received less support than the mother and his special role in the life of the visually impaired infant has not been emphasized. If the family breaks and there will be two families involved in the early care of the child, this should be met with increased support to ensure a balanced growing and development of the infant and the family.

Slide 4.

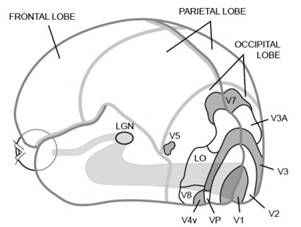

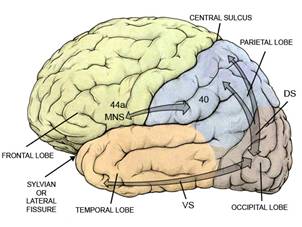

Slide 5.

Since we will be talking about development and assessment of visual functions in infants and children with damage to the visual system, it is pertinent to briefly describe visual pathways. Changes due to diseases, trauma or malformations may occur in any part of the anterior pathways, a) eyes, optic nerves, b) lateral geniculate nucleus or optic radiations or in the brain, c)visual cortices in the occipital lobe altering the early processing, d) in the parietal networks (dorsal stream), e) inferotemporal networks (ventral stream) or f) mirror neuron system (MNS). Neural activity that carries visual information from the eyes to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) undergoes major changes in the LGN due to information that returns from the visual cortex and functions like a filter decreasing and modifying visual information. Activity in several structures around the LGN also causes changes in the visual information flowing into the primary visual cortex, V1. Visual pathways are a two way street. More detailed information on the visual pathways and brain functions is in the lecture Visual Pathways. In infants and children with brain damage, the changes may have affected the development anterior visual pathways or of cortical structures and connections between different parts of the brain so that the anatomy and functioning of brain is difficult to understand before the child is a teenager and is motivated to participate in complex laboratory examinations.

Following case history is an example of combining early surgical care of an ocular condition and the early intervention of the infant and family:

The baby was born with cloudy corneas due to congenital glaucoma (Slide 6). Opening of the eye lids did not change her vision so she kept her eyes shut. Corneal transplant in the left eye was not tolerated by the body; the clear transplant became cloudy. The glaucoma operation failed also, the eye lost pressure. Corneal transplant in the right eye was clear from the fifth to the fifteenth week and became then cloudy. Immediately after the operation of the right eye the baby received near spectacles and started to use her vision. In the ten weeks when the clear cornea allowed the baby see details she caught up with the delay in the motor development and thereafter developed quite normally although she could see only bright colours, shadows and movement, no small forms. She is now adult, has university degree and works. Sometimes the time of good vision after operation is short and therefore it is wise to start early intervention with supportive training without delay.

Slide 6.

If the loss of vision is caused by a cloudy cornea, we can simulate the quality of vision by looking through a translucent material and can understand the structure of the visual information available to the child. If the loss of visual functioning is in one or a few cortical functions, the behaviors of an infant and child are difficult to understand because the child seems to have normal vision but does not use it in all tasks or activities.

Slides 7 and 8: There are several problems areas that should be considered, especially if the infant is the first child of the parents:

- Parents may have no experience of atypical development

- Treatment of diseases and disorders disturbs interaction in the family

- Immediate contact with early intervention should be arranged

- Assessment of visual functioning should be a part of early treatment

- Assessment of general functioning should be thorough

- Assessment of the needs of each family is individual

When an infant’s eye(s) must be operated and a successful result cannot be promised, the parents go through an emotionally difficult time. The time of operation is also difficult to the baby who does not experience the normal warmth and security of the mother’s lap but strangers and pain. Often the infant is the parents’ first child. Parents may have little or no experience of visual impairment or blindness. Care of a blind infant is difficult to imagine. Early intervention worker should be present in the hospital to support the parents in their anguish and worries and help them to start early communication without normal eye contact and to enjoy all the functions that the infant has.

Immediate contact with early intervention is not the rule in many hospitals. It is usual that the parents get information about the eye or vision disorder and how to take care of the treatment at home but do not meet an early intervention worker for visually impaired infants even if the infant were/was several days in the hospital. If there is no surgical or medical treatment, the parents may hear that “there is nothing to be done”, which is not true. A lot should be done. Parents may get a phone number where to call for a worker at the National Association for the Visually Impaired and Blind or a local service. That phone call is often postponed for weeks because the parents do not have the strength to meet one more person related to vision loss.

Many infants with vision problems have more noticeable disorders that can be diagnosed at birth. The groups of newborn and young children at risk of having problems in visual functioning are: infants born prematurely (retinal changes, brain damage) and infants with brain damage and structurally normal eyes; infants with syndromes, Down syndrome being the most common syndrome; all deaf infants; all hypotonic infants even if no obvious cause has been diagnosed.

Assessment of vision or refractive errors is not included in the routine early care in most hospitals, thus weak accommodation and/or uncorrected refractive errors can disturb early communication and interaction. Early intervention as support to the parents should start as an integral part of treatment; at birth if visual impairment is noticed during the first day. First information is an important part of early intervention and should be given by an experienced ophthalmologist and pediatrician or pediatric neurologist.

The follow-up of vision related functions as a part of follow-up of the development of infants has the same milestones in all Western countries: at the age of 6 weeks the infant should have good eye contact with parents and 2-3 weeks later an active visual interaction (Slide 2 in Pittsburgh).

Slide 9.

Eye contact and copying of facial expressions can start at birth and should have started in a healthy baby at the age of 6 weeks, which is a usual time for home visit by the health care nurse or visit at the health care center. If the infant does not have a normal eye contact, we usually do not wait more than two weeks. If the eye contact has not become normal, the infant is referred to the consulting ophthalmologist without delay. If the examination does not find anything wrong in the eyes, the infant is referred to the pediatric neurologist with the question “Why does the brain not use vision that seems to be present?” Social smile and active interaction with the parents have usually developed at the age of 12 weeks and are integral components in the development of emotional bonding between the baby and her/his parents.

Slide 10.

If a 4-month-old baby refuses visual communication with her mother we can guess that either the image that the infant sees is unpleasantly blurred or distorted, possibly also double or the mirror neuron system that supports copying of facial expressions and feeling-in to the other person’s emotional state has not started to work.

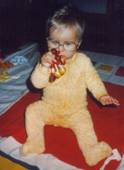

In this infant the cause was blurred image on the retina because the infant could not focus the lens, accommodate. For some reason the tiny group of cells in the brain that should be active and automatically focus the lenses had not started to function. Therefore “reading glasses”, near correction lenses were placed in front of the baby’s eyes to give a clear picture of the mother’s face, on the retina. In a few seconds there was a change in the baby’s behavior: she looked at the mother’s face, first surprised, then the eyes converged and the baby smiled for the first time in her life. Mirror neuron system functioned when the image was clear enough. Testing for the effect of near correction to the communication of each infant with delay in eye contact, especially of each hypotonic infant is one of the messages that I would like to leave to each of the readers.

Slide 11.

Weak accommodation can and should be compensated with ”reading glasses”. – Sometimes I hear doctors saying that “the vision of a young infant is not so sharp that blur should disturb it”. Vision is not of poor quality, visual acuity is not high but perception of low contrast shadows in motion on the face is sufficient to make early visual communication and interaction possible, as we have just seen. Near correction should be given early.

In all countries we find now school children with CP and/or intellectual disability who have only distance correction, no reading parts in their glasses or no glasses. It is sad to meet children with variations of the following history: the child did not have eye contact as young infants, remained distant in visual communication, and did not use vision for exploration but developed good tactile skills like blind children. In most cases these children received their first glasses at the age of three years, slightly undercorrected distance correction for +6 to +8 diopters at the same time as they got their diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder. They used their vision better at distance but did not look at objects at close distances and remained highly tactual, which was interpreted as a typical autistic behavior. When we meet these children at school age, some of them have constant diplopia that they have not been able to describe (not knowing how other children see) and most of them have problems in moving down on stairs and recognizing people’s faces(due to low contrast sensitivity) and great difficulties in learning to read and write.

Near vision improves notably and diplopia disappears with proper spectacles, which makes school work easier. It is sometimes possible to train the child to become aware of facial structures and expressions but the content of expressions remains (as) “a foreign language” and the normal instant awareness of other people’s emotional state when looking at their faces rarely developed. It should start to develop early during the first year of life. Therefore it is always important to see to that every infant receives the best possible near correction for visual communication if it is not developing normally and that the parents are supported in creating effective, emotionally warm communication using other senses.

Slide 12.

Late development of accommodation may lead to esotropia, which requires glasses with special structure: in this case bifocal for the left eye and near correction lens for the right eye, which blurs the image at distance (called ”penalisation”). With this correction the infant in Figure 11 had “straight” eyes at near distances and did not see double when looking at distance even if the right eye was turned inward because the image was blurred. The infant developed normal binocular vision. At school age esotropia remained but was corrected with progressive glasses. No patching or surgery was needed.

Slide 13.

Early assessment team of infants and children with vision loss and other impairments can grow so big that it causes an additional problem to the family. Few of us have the stability of mind that we can calmly discuss our child’s care and development with a dozen specialists who may have slightly different opinions on the child’s treatment. Numerous contacts with specialists, changing nurses and therapists in the hospital cause stress to the infant and her/his parents. Stress negatively affects development of brain and repeated painful procedures may cause peaks in blood pressure, which may lead to bleeding in the fragile vessels of the brain.

Ideally, one or two pediatric specialists should report the laboratory findings and information from the consultations to the parents and the early intervention worker who then discusses the findings with parents further, also the practical consequences.

Slide 14.

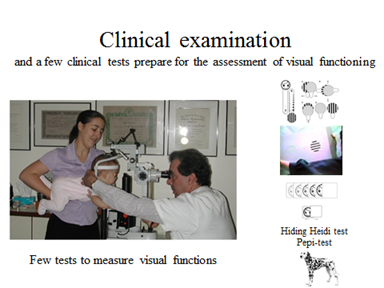

Clinical examination by an ophthalmologist and his/her team is the foundation for assessment of visual functioning. When assessing infants we have few tests available and therefore examination of the structure of the eyes and ocular motor functions and alignment of the eyes are especially important. Responses to gratings measured using Teller Acuity Cards or LEA GRATINGS depict detection of gratings but we do not know how the infant perceives the gratings – as straight or distorted lines. – These “response to grating”- values should NOT be converted to recognition acuity values measured using optotype tests. When the true grating acuity values can later be measured, they should not be converted to optotype acuity values either. Grating acuity and optotype acuity measure vision in two different ways.

Slide 15 and 16.

Hiding Heidi test is a preferential looking-test and was designed to assess communication distance, the distance where the infant/child can respond to visual communication. If a 3 month old infant responses with a typical social smile we learn about several brain functions: the infant has perceived the picture well enough to follow its slow movement but he has also perceived the picture as a smiling face because he responds to it. This response means that his mirror neuron system functions and he can use his facial musculature for the response. In this brief moment we have observed several important brain functions in vision, motor and emotional development.

For the communication distance we measure at which low contrast (5% or 2.5%) the child follows the picture and fixates it similar to the high contrast pictures (25% and 10% contrast). If the response to the low contrast pictures occurs only at distances that are shorter than the usual communication distances, adult people need to increase contrast on their face, i.e. use make-up (men: contour pen) and use slower and clear pronunciation. (Nobody whispers to hearing impaired infants – why do we use low contrast visual information for visually impaired infants?!)

If the child does not follow the low contrast pictures (5% and 2.5%) at the usual communication distance we know that we must be close to the infant and add contrast on the face so that the infant gets sufficient visual information for communication. Facial expressions are fast moving faint shadows on the face, thus we, and infants, need low contrast information and motion perception to perceive them. If it is uncertain how well the infant can perceive facial features and follow lip movements, use of tactile information in communication should be started early. The little hand cannot feel both lip movements and vibration of the vocal cords (Tadoma technique of adults) so the hand is guided to feel parents’ lips and neck when they are talking. Faces of parents should always be explored regularly by the infant’s hands so that people become more concrete, are not only voices. Fathers are especially interesting: 1) as the first thing in the morning he can help the baby to carefully feel the face, 2) shaves half of the face, after which the baby explores the face, 3) shaves the other half and the baby explores again, 4) when the father comes home he again explores the face with the baby. Mothers never change like fathers.

Slide 17.

The child in Figure 17 had no head control in the midline, the head fell against the pillow on one or the other side. Long narrow pillow gave good head support for using eye movements. The child had very poor accommodation and moderate hyperopia and thus needed proper near correction in well-fitting frames to see the test pictures. Skin on his face was hypersensitive, which you can notice in the video when the glasses are placed in front of his eyes. When the frame does no more move it does not disturb. This kind of a child’s response is often erroneously interpreted that the child refuses to have glasses on his face. Hypersensitivity can be decreased by using a wash cloth around the child’s hand and rubbing with it the face, first a soft cloth, then slowly increasing the roughness of the wash cloth. When child rubs him-/herself it is more acceptable than if rubbing is performed by an adult.

Pepi-test is a figure-in-motion-test that you can perceive as long as it moves. In the test there are first red-white lines in the middle of the screen to observe fixation. Next, Pepi picture appears in a corner. If the infant/child notices it, a saccade to that corner reveals it. When the picture moves across the screen you can observe the eye movement following the picture. In the video you see both the quick saccades to the corners of the screen and especially clearly the movement of the right eye to right and up. If an infant’s picture recognition or motion perception is weak, he sees only “something moving” and soon loses interest. If the dog is clearly seen, the infant/child keeps looking for the picture to appear more than the first four presentations in different directions, which gives you time to observe eye movements in a visual task that the child enjoys.

Whatever animal or object the child mentions; remain neutral and say “That was what you saw.” “Should I play this video again?”